I’m not much of a planner. This is not a philosophical stance, just the way my brain works. I jump with both bare feet into whatever stream interests me. I don’t pick the best spot on the stream or check the speed of the current. I go. It’s only after I’ve experienced some of the stream that I consider how I might go about it the next time I get in. This is also how I go about writing my stories.

Many of my story ideas arrive out of an image or a question. I heard a story about a husband who stole a child’s wrapped birthday present, and his wife covered it up for him. How did that happen? What was the motivation? In another instance, I saw a dead dog on a sidewalk and found myself thinking about social media posts. But those are starting points, plot elements. They don’t tell me what the story is deeply about.

Curiosity Over Predeterminism

I believe that to write a good story–and by ‘good’ I mean unexpected, provocative, unvarnished–that our ego, our desire for certainty or brilliance is put aside. I find that when I plan my story, I lose my curiosity about it because I already know what will happen and how the characters will react. They’ll do my bidding. It’s like playing with paper doll cutouts.

“When I plan my story, I lose my curiosity about it because I already know what will happen… it’s like playing with paper doll cutouts for me.”

At about the midway point, sometimes earlier, I articulate the story’s center and jot down what I believewill happen. But I don’t get caught up in adhering to that plan, and I don’t outline when I’ll introduce a character or when I’ll change points of view.

Outlines Can Be Necessary and Useful

Cameron’s post on his process discussed the insanity of such a process. He believes an outline is a story’s skeleton. “You won’t win the marathon, which is your finished novel, with your skeleton

alone, but I dare you to try winning without it!” I see his point. A writer could quickly get overwhelmed and frustrated. Building an outline, knowing what comes next keeps things manageable and clear. With plot-centric novels, part of the writer’s job is directing traffic, and an outline is very useful to that end, especially when a work is part of a series or contains multiple volumes.

Recently, when I wrote the book, or script, of a musical, I made a plot synopsis for the composer well before I had written the first scene. My final script adhered to about 70-percent of that synopsis. I enjoyed knowing what I needed to write next, but my writing was stilted. I had to work to invest in the characters before the script began to come alive.

Ultimately, writing stories is a discovery process in which I tease out the story’s scenes and interactions that have the most energy. For instance, I initially thought the birthday present story was about the wife. Then, without any intention, I found myself curious about the children and wrote two scenes from their point of view. The kids’ scenes bristled with energy, and complicated the narrative. Without it, the story plodded along. Had I not trusted my wandering, I never would have written those scenes with the kids.

I’m Not the Only One

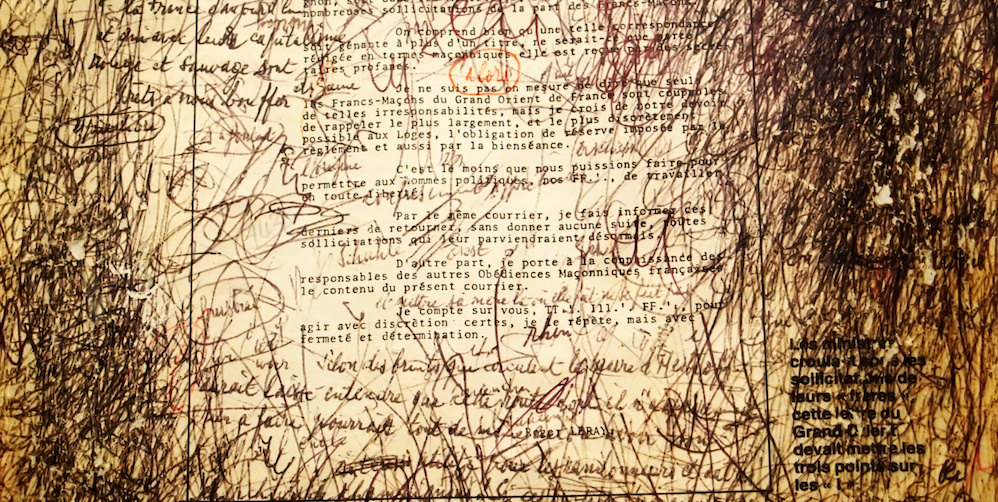

Author Lauren Groff told Guernica Magazine in 2013 that she writes multiple first drafts of her novels on notebooks and legal pads, and she never looks back at any of them, just starts over.

“Our human impulse is to control everything, but fiction seems to me to be about allowing an element of mystery into the text,” she told the magazine. Handwriting her work is a means of allowing that mystery. Her first novel was written over and over from different points of view. If what she has written is any good, she believes, that scene or phrasing will come back to her in the next draft. Note, she doesn’t plan her novels. She lets them go wherever they go.

Essentially, hers is the iterative process, one all kids practice when building a fort or catching a ball. I feel a kinship with that approach because it is as invested in the process, in the play of writing, as it is the result.

Social